Bowel Cancer Explained

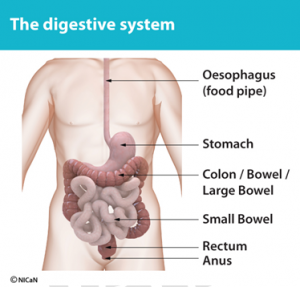

The digestive system

To understand bowel cancer it helps to have some knowledge of how your body works. When food is eaten, it passes from the mouth down the oesophagus (food pipe) into the stomach. Here it is broken down and becomes semi-liquid. It then continues through the small intestine (small bowel), a coiled tube many feet long where food is digested and nutrients (things your body needs) are absorbed (see diagram below).

The semi-liquid food is then passed into the colon (large bowel), a wider, shorter tube, where it becomes faeces (stools). The main job of the colon is to absorb water into our bodies making the faeces more solid. The stools then enter a storage area called rectum. When the rectum is full, we get the urge to open our bowels. The stools are finally passed through the anus (back passage) when going to the toilet.

What is cancer?

The tissues and organs of the body are made up of cells. These age and become damaged and need to repair and replace themselves continually. Normally, this takes place in a structured and orderly fashion. Sometimes, this process goes wrong and cell division and repair gets out of control and a growth forms. This growth is called a tumour. A tumour may be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). In a benign tumour the abnormal cells develop to form a growth but do not spread, although the tumour can become large and press on other organs. A malignant tumour can spread to invade and possibly destroy surrounding tissues. Cancer cells can also spread to other organs in the body through the blood stream or the lymph glands. The cells can continue to grow and form a new tumour in another place, which is often called a ‘secondary’ or a metastasis. Cancer is not a single disease with a single cause and a single type of treatment. There are over two hundred types of cancer, each requiring different treatments.

What is bowel cancer?

The term ‘bowel cancer’ is used to describe both:

- Cancer of the large bowel (colon)

- Cancer of the back passage (rectum). These cancers are known as colorectal cancers.

How does bowel cancer develop?

Little is known regarding the cause of bowel cancer, although we are aware of some risk factors. Most of these are associated with lifestyle:

What causes cancer of the bowel?

- Bowel cancer usually develops from a polyp in the bowel. A polyp is a type of growth that forms in the lining of the bowel. Most polyps remain benign but, if left untreated, some may turn into a cancerous tumour. Removal of polyps can prevent bowel cancer.

- ‘Western’ type diet – high meat intake (particularly processed meat: sausages, bacon, burgers and ham). Low intake of vegetables and possibly fruit.

- Inactive lifestyle.

- Smoking.

- Obesity.

- Some inflammatory bowel diseases.

- A family history of bowel cancer – if two or more members of your immediate family have had bowel cancer or one member of your family was diagnosed under the age of 45.

What are the symptoms of bowel cancer?

Symptoms vary according to the position and size of the cancer. The following can be possible symptoms of bowel cancer and include:

- A persistent change in bowel habit for six weeks such as: going to the toilet more often, or trying to go, looser or more diarrhoea like stools or severe constipation.

- Repeated bleeding from the back passage or blood in the bowel motion with no anal symptoms (no irritation lumps, straining with hard stools or soreness).

- Unexpected weight loss.

- Anaemia (unexplained tiredness and fatigue due to a low level of red blood cells).

- An unexplained lump in the tummy.

These symptoms do not definitely mean that someone has bowel cancer, however, they should always be taken seriously.

How do I know I have bowel cancer?

Bowel cancer is usually diagnosed using the results from a number of tests and investigations:

- Tests with a specialised flexible telescope to look inside the bowel.

- X-ray tests and scans.

- Blood tests.

How is bowel cancer treated?

There are three standard types of treatment for bowel cancer. These are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Each of these can be used alone or in combination with each other, depending on the extent and location of the disease. When a diagnosis of bowel cancer is made, each individual case is discussed at a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting where cancer specialists consider which treatment(s) may be the best option. Following the MDT meeting your consultant surgeon will discuss the results of your investigations and treatment options with you. Your surgeon will also answer any questions you have on the benefits and risks of these treatments. Once a treatment plan has been agreed with you, the team should be able to offer you a date to start treatment within 31 days.

What type of surgery is performed?

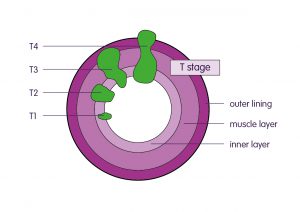

The type of operation performed depends on the extent and position of your cancer. Where possible the cancer and surrounding bowel and tissues will be removed and the two ends of the bowel joined back together. Sometimes a stoma (bag on the tummy to collect bowel waste) may need to be performed; this can be temporary or permanent. Following surgery a pathologist examines the piece of bowel removed. The pathologist describes the growth of the cancer according to a system called the TNM syatem. This is explained in the picture below:

Image: Bowel Cancer UK.

TNM system

- T (tumour) – how far the tumour has grown through the bowel wall

- N (nodes) – whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes

- M (metastases) – whether the cancer has spread (metastasised) to other parts of the body

T stage

- T1 – the tumour is in the inner layer of the bowel

- T2 – the tumour has grown into the muscle layer of the bowel wall

- T3 – the tumour has grown into the outer lining of the bowel wall

- T4 – the tumour has grown through the outer lining of the bowel wall

N stage

- N0 – no lymph nodes contain cancer cells

- N1 – cancer cells in up to three nearby lymph nodes

- N2 – cancer cells in four or more nearby lymph nodes

M stage

- M0 – the cancer hasn’t spread to other parts of the body

- M1 – the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, like the liver or lungs

What is radiotherapy?

Radiotherapy involves directing a beam of radiation at the cancer; it is similar to having an X-ray. Radiotherapy is usually given on a daily basis as an out-patient over a period of time. Radiotherapy is carried out and The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, in Birmingham. Each treatment takes just a few minutes to complete and is painless. Courses of treatment are short (five days) or long (four to six weeks).

Radiotherapy can be used to:

- Shrink rectal cancer prior to surgery.

- Relieve symptoms if surgery is not appropriate.

- Reduce the risk of a cancer coming back after surgery.

- Treat cancer if it comes back after surgery.

Click here for Macmillan information on Radiotherapy

What is chemotherapy?

- Chemotherapy is a systemic treatment in that it treats the whole body. It involves the use of anti-cancer drugs to destroy cancer cells or stop them from multiplying.

- Chemotherapy may be given with long course radiotherapy before surgery.

- Chemotherapy given after surgery is usually over a period of about six months as an out-patient.

- Sometimes chemotherapy is used instead of surgery if an operation is judged not to be suitable.

- Drugs may be given by injection into a vein or by mouth in a tablet form. Often people who have seemingly the same disease have different treatments. This is because tumours can be of different sizes, different types and in different parts of the bowel and/or body. If chemotherapy is suggested, a consultant oncologist will explain which anti-cancer drugs are suitable for you and discuss the aims of treatment and any possible side effects.

For some patients the cancer is too advanced or has spread in such a way that surgery to remove it is not feasible or appropriate.

There may still be treatment with our Oncologist with anti-cancer therapy to try and control the cancer for as long as possible.

There are numerous support mechanisms for patients in this setting both within the hospital and in the community and with the support we can enable you to remain as well and independent as possible. We can refer you for these if appropriate; please contact the colorectal clinical nurse specialist or your oncologist for more information.

Click here for Macmillan information on Chemotherapy

What are clinical trials?

We keep personal and clinical information about you to ensure you receive appropriate care and treatment. Everyone working in the NHS has a legal duty to keep information about you confidential. We will share information with other parts of the NHS to support your healthcare needs, and we will inform your GP of your progress unless you ask us not to. If we need to share information that identifies you with other organisations we will ask for your consent. You can help us by pointing out any information in your records which is wrong or needs updating.

Click here for Macmillan information on Clinical Trials

Our commitment to confidentiality

This information was originally developed by a range of health care professionals and the copyright was through the former Pan Birmingham Cancer Network. The information has now been adopted by Good Hope, Heartlands and Solihull which are part of University hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust and reviewed and revised in line with trust policy. If you have any questions at all, please ask your consultant surgeon, oncologist or colorectal nurse. It may also help to write down questions as you think of them so you have them ready and bring someone with you when you attend your outpatient appointments. Research is continuing to find new or better ways of treating bowel cancer. All new drugs and treatments are developed through clinical trials. You may be asked to participate in these. This is completely voluntary and would be discussed with you in detail.

For further information please click on links below:

Macmillan Information about bowel cancer

Bowel Cancer UK Charity – Understanding bowel cancer

Bowel Cancer UK patient information leaflets

Young persons guide to bowel cancer

BBC journalist George Alagiah hosts a podcast, interviewing supporters and leading experts on the disease, as well as discussing his own treatment and diagnosis.